In this video, we discuss an interesting study from Taiwan. The study examines possible connections between the Schumann resonance and insomnia.

Sleep disorders are among the most common health problems of our time. A recent study by experts examines the connection between the natural Schumann resonance – electromagnetic vibrations of the Earth – and insomnia. The results provide exciting insights into the possible influences of natural frequencies on human sleep.

Yu-Shu Huang (1,2), I Tang (1), Wei-Chih Chin (1,2), Ling-Sheng Jang (3), Chin-Pang Lee (1,2), Chen Lin (4), Chun-Pai Yang (5,6), Shu-Ling Cho (7)

(1) Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Sleep Centre, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan;

(2) Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Taoyuan, Taiwan;

(3) Department of Electrical Engineering, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan;

(4) Department of Biomedical Sciences and Engineering, National Central University, Taoyuan, Taiwan;

(5) Department of Neurology, Kuang Tien General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan;

(6) Department of Nutrition, Huang Kuang University, Taichung, Taiwan;

(7) Department of Clinical Psychology, Fu Jen Catholic University, New Taipei City, Taiwan;

Numerous studies have shown that electromagnetic fields can influence the human brain and sleep, and that

extremely low-frequency electromagnetic fields, known as Schumann resonances, may help alleviate sleep disorders

. The aim of this study was to investigate the responses of patients with sleep disorders to non-invasive treatment with Schumann resonances

(SR) and to assess its effectiveness using subjective and objective sleep assessments.

We used a double-blind, randomised design, and 40 participants (70% female; 50.00 ± 13.38

years) with sleep disorders completed the entire study. These participants were divided into the SR sleep device group and the placebo device

group and observed for four weeks. The study used polysomnography (PSG) to measure objective sleep and used sleep diaries, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and a visual analogue of

sleep satisfaction to measure subjective sleep. The 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) was used to assess quality of life. The chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon test were used to analyse the data.

Approximately 70% of the subjects were women with an average age of 50 ± 13.38 years and an average history of sleep disorders of 9.68 ± 8.86 years. We found that in the SR sleep device group, the objective sleep measurements (sleep onset latency, SOL, and total sleep time, TST) and subjective sleep questionnaires (SOL, TST, sleep efficiency, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness and sleep satisfaction) were significantly improved after using the SR sleep device; in the placebo device group, only subjective sleep improvements such as PSQI and sleep satisfaction were observed.

This study demonstrates that the SR sleep device can reduce the symptoms of insomnia through both objective and subjective tests with minimal side effects. Future studies may investigate the potential mechanism of SR and its impact on health, and verify its efficacy and side effects with a longer follow-up period.

Insomnia, Schumann resonance, effectiveness, polysomnography, questionnaire

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder worldwide, affecting up to 10% of the total population and approximately 15% of adults (1). According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3), insomnia is defined as

(1) Difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or waking up before the desired time;

(2) Sleep disorders that cause significant personal distress or impairment in daily life; and

(3) Sleep disturbances and associated daytime symptoms occurring at least three times a week over a period of at least three months.

Insomnia encompasses not only sleep disturbances at night, but also impaired daytime functioning, such as fatigue, attention and memory problems, impaired social, academic or occupational performance, and mood swings.

Furthermore, many studies have shown that people with insomnia have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic pain and type II diabetes.

Furthermore, the comorbidity rate of insomnia and other mental disorders is 41–53%.

After cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBTi), patients with comorbid mental disorders not only experience improved symptoms of insomnia, but also improved symptoms of their comorbidities.

Although the pathophysiological characteristics of insomnia are largely unknown, there is growing evidence that insomnia is a persistent condition and a complex disorder. A cohort study of 3,073 adults who were followed up annually over a period of 5 years confirmed that 41.6% of participants suffered from persistent insomnia. This finding suggests that early intervention could prevent the development of chronic insomnia and reduce the associated morbidity from sedatives and sleeping pills.

Previous studies have shown that up to 13% of adults in the United States reported having taken benzodiazepines in the past year. Outpatient use of benzodiazepines has also increased significantly. Long-term use and overdose of sleeping pills can lead to side effects.

Although guidelines for the treatment of insomnia include established recommendations for clinical practice regarding CBTi as first-line treatment, this treatment method has not yet become established in many countries. Furthermore, patient inconvenience and compliance with CBTi remain key issues in the implementation of this treatment. It is therefore important to investigate the effectiveness of other and newer non-pharmaceutical treatments for insomnia.

In recent years, various non-invasive treatment methods for insomnia have been researched, including mindfulness therapy, acupressure, acupuncture therapies, cranial electrotherapy stimulation (CES) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), etc. Another notable discovery of the last 20 years is that electromagnetic fluctuations in the environment, such as geomagnetic activity, can influence our physiology, psychology and behaviour. Earlier physical research showed that ‘electroencephalographic performance showed certain correlations with the right parietal lobe for theta activity and the right frontal region for gamma activity.’ Some studies have shown moderate correlations between an increase in geomagnetic activity and various behavioural consequences of brain activity.

Wang et al. (2019) used an electroencephalogram (EEG) study and reported a strong, specific response of the human brain to ecologically relevant rotations of the Earth’s magnetic fields. After geomagnetic stimulation, there was a repeated drop in the amplitude of EEG alpha oscillations (8–13 Hz).

In 1954, Winfried Otto Schumann reported on the existence of a natural extremely low-frequency field of approximately 7.83 Hz, known as the Schumann resonance frequency (SR), in the Earth’s atmosphere, which propagates electromagnetic waves (EMW) globally. 27 Its peak intensity can be detected at ~8 Hz, along with its harmonics with lower intensity at 14, 20, 26, 33, 39 and 45 Hz due to frequency-related ionospheric propagation losses.

The Schumann resonances found in both the global quantitative electroencephalographic activity of humans and the activity of the Earth’s ionosphere could indicate a causal relationship.

Furthermore, Ghione et al. found significant positive correlations between geomagnetic activity and systolic blood pressure (during the day and over 24 hours) as well as diastolic blood pressure (during the day, at night and over 24 hours). Burch et al. also found that increasing geomagnetic activity associated with elevated 60 Hz MF is associated with reduced nocturnal excretion of a melatonin metabolite in humans, meaning that EMF affects the human brain and sleep.

In light of these findings, extremely low-frequency EMF Schumann resonance could improve human sleep. In this study, we use a sleep device with a ‘Schumann resonance’ function that emits the low frequency of the ‘Schumann resonance frequency (7.83 Hz) wave’ to resonate with the user’s brain waves, thereby facilitating falling asleep, reaching deep sleep and maintaining sleep. As the efficacy and side effects of ‘Schumann waves’ in the treatment of insomnia are still unclear, this study aimed to investigate the effects of Schumann resonance on insomnia symptoms through subjective and objective sleep assessments.

In this study, patients with insomnia were recruited through outpatient clinics at hospitals, and 46 participants met the inclusion criteria and took part in the study after giving their informed consent. Of these, four withdrew because they were unable to attend the follow-up appointment, and two participants suffered from headaches and dizziness after randomisation and discontinued the follow-up. A total of 40 participants completed the study. The study was conducted by Chang 1114 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S346941 Nature and Science of Sleep 2022:14 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) DovePress Dovepress Huang et al Gung Hospital IRB: No. 201701063A3 and No. 202101267B0 (clinical trial ID: NCT05053919, study period: 27 July 2021 to 19 January 2022) and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The inclusion criteria are: (1) participants aged between 20 and 70; (2) participants must meet the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for insomnia and have been diagnosed for more than three months; (3) participants must be willing to sign a consent form; and (4) participants taking sleep medication must agree not to make any changes to their medication or dosage during the study.

Exclusion criteria include (1) participants who use pacemakers or cardiac monitors; (2) participants with serious physical illnesses or who have undergone surgery, such as heart disease, metabolic disorders or cancer; (3) participants with serious mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, severe major depression, severe anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, dementia, substance abuse; or serious neurological disorders, such as seizures, stroke or Parkinson’s disease; (4) Participants with other severe sleep disorders, such as severe obstructive sleep apnoea, severe periodic limb movement disorder or narcolepsy; (5) Participants who are unable to attend follow-up examinations regularly; and (6) Participants who are unable to maintain good sleep hygiene and are unable to refrain from using electronic devices before bedtime.

This study is a randomised double-blind case-control study. All participants who met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to either the ‘SR sleep device group’ or the ‘placebo device group’. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of background variables such as gender ratio, age and duration of insomnia.

All participants were randomly assigned to two groups and used the ‘sleep device’ for four weeks.

The primary endpoint is changes in polysomnography, and the secondary endpoints are changes in subjective questionnaires, including the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI) and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), sleep diaries, the visual analogue scale for sleep satisfaction, and the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36).

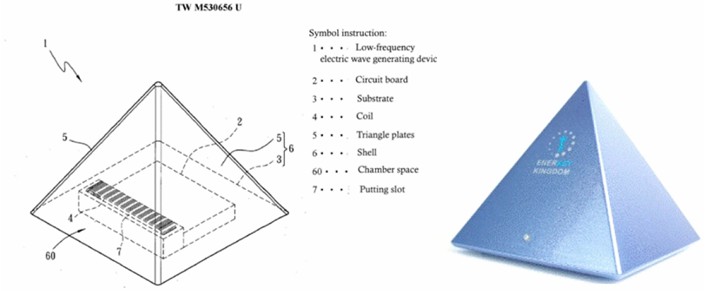

The SR device was developed by Professor Ling-Sheng Zhang of National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan (Figure 1: ‘Enerkey Kingdom SR Sleep Device’). The sleep device was capable of generating the ‘low-frequency Schumann resonance frequency (7.83 Hz) wave’ and was granted a Taiwanese patent (No. TW M530656U) on 4 May 2016. After switching on the sleep device, it steadily emits the composite frequency of the ‘Schumann resonance frequency (7.83 Hz) wave, theta wave and delta wave’. A placebo device is a device that looks and functions exactly like the SR sleep device, but does not emit any frequency waves. The test subjects were asked to use the device every night for four weeks (placing it next to the bed towards the test subject’s head, switching it on about an hour before bedtime each evening and switching it off the next day after getting up) and to record their sleep in sleep logs.

A standard nocturnal PSG was performed to document the sleep of all participants before using the SR sleep device/placebo device and four weeks after use. Participants were asked to arrive at 9 p.m., were led to the examination room by a sleep technician, where they were fitted with a sensor device, and lay down on the bed at 10 p.m. The examination ended at around 6 a.m. the next morning. The standard overnight polysomnographic examination included systematic monitoring of the following variables: 4 EEG leads, 2 electrooculogram (EOG) leads, chin and leg electromyogram (EMG) leads, and 1 electrocardiogram (ECG) lead (ECG); respiration was monitored using a nasal cannula pressure transducer, an oral thermistor, inductive plethysmography bands for the chest and abdomen, a finger oxygen saturation monitor (MasimoTM) with oximetry and finger plethysmography signal recordings, a throat microphone, diaphragmatic-intercostal and abdominal muscle EMGs, and a transcutaneous CO2 electrode; In addition, leg EMGs were monitored. The subjects were continuously monitored by video during the recording. The recordings were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), and the PSG evaluation was also performed in accordance with the AASM recommendations, with hypopnoea being assessed either at a 3% drop in oxygen saturation or at an arousal response.

Participants completed sleep diaries daily for two weeks prior to using the SR sleep device/placebo device and for four weeks while using the device to record their sleep. An estimate for the average SOL, TST, SE, and WASO was calculated from the diaries.

The PSQI is a questionnaire for self-assessment of subjective sleep quality, consisting of 19 questions that can be calculated and combined into 7 clinically derived component scores (0–3), with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. 33,34 Participants completed the PSQI before use, two weeks after use, and four weeks after use of the SR sleep device/placebo device.

The ESS consists of 8 items (each scored from 0 to 3) and was used to assess daytime sleepiness in individuals. Thirty-five participants completed the ESS before use, two weeks after use, and four weeks after use of the SR sleep device/placebo device.

The subjects were also asked to rate their satisfaction with their sleep during the past week on a seven-point scale before use and four weeks after use (a higher score indicates greater satisfaction with sleep).

The SF-36 comprises 11 key questions that assess eight components. These components include physical functioning, limitations due to physical health, limitations due to emotional problems, energy/fatigue, emotional well-being, social functioning, pain and general health. The scale can be used to assess a patient’s overall quality of life. Higher scores indicate better physical or mental functioning.

We analysed our data using SPSS 22.0. The data were presented as numbers, means, percentages and standard deviations. We used the chi-square test for group comparisons of percentages and the Mann-Whitney U test to analyse the differences in objective and subjective measurements between the SR sleep device group and the placebo group. We used the Wilcoxon test to analyse the differences before and after using the device. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

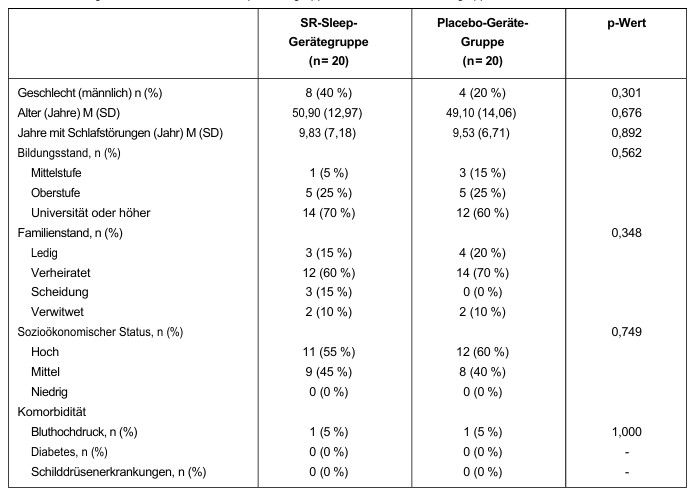

Approximately 70% of the 40 subjects were women with an average age of 50 ± 13.38 years and an average history of sleep disorders of 9.68 ± 8.86 years. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the participants at the start of the study. No significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of gender, age, duration of sleep disorders, educational level, marital status, socioeconomic status or comorbidity.

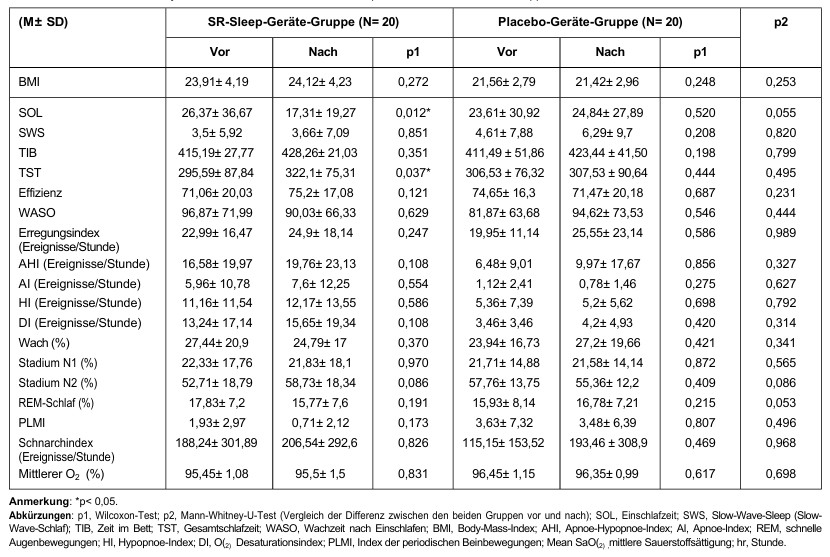

Comparisons of objective sleep measurements before and four weeks after using the SR sleep device/placebo device are shown in Table 2. In the SR sleep device group, a significant reduction in SOL (p = 0.012) and a significant increase in TST (p = 0.037) were observed. No significant difference was observed in the placebo device group. Although there was no significant difference between the two groups before and after treatment (Mann-Whitney U test), there was a trend for many parameters in the SR sleep device group to improve, particularly SOL (p = 0.055).

Table 1: Demographic data for the SR Sleep device group and the placebo device group

Table 2: Differences in objective PSG findings in the SR Sleep device/placebo device group

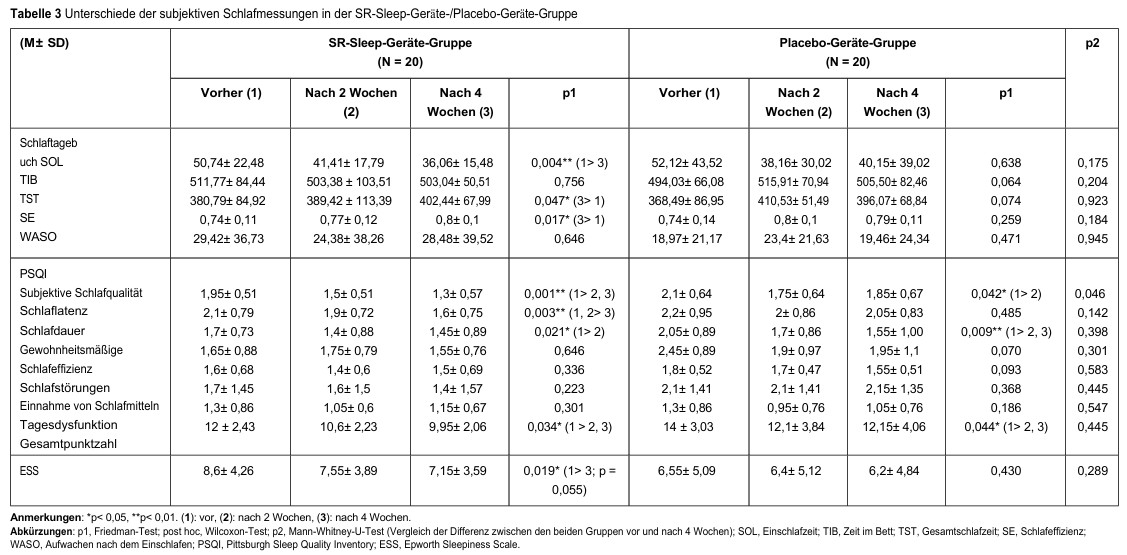

Comparisons of subjective sleep measurements before, two weeks after, and four weeks after using the SR sleep device/placebo device are shown in Table 3.

In the SR sleep device group, a significant reduction in SOL (p = 0.004) and a significant increase in TST (p = 0.047) and SE (p = 0.017) were observed (all differences existed between the pre-test and week 4). No significant difference was observed in the placebo device group.

Eine signifikante Verringerung des Schlaflatenzindex (p = 0,003, die Signifikanz lag zwischen „vorher, Woche 2” und „Woche 4”) wurde in der SR-Schlafgerät-Gruppe beobachtet, nicht jedoch in der Placebo-Gerät-Gruppe. Signifikante Verbesserungen des subjektiven Schlafqualitätsindex (pSR = 0,001 (vorher > Week 2, week 4); pplacebo = 0,042 (before treatment > Woche 2)), des Schlafdauerindex (pSR = 0,021 (vor der Behandlung > Week 2); pplacebo = 0,009 (before treatment > Week 2, week 4)), of the overall index (pSR = 0,034 (before treatment > Week 2, week 4); pplacebo = 0,044 (before > Week 2, week 4)) and ESS (pSR = 0,019 (before > Week 4, p = 0,055)) were oberved in both groups. In addition, the ‘sleep quality’ parameter improved significantly in the SR sleep devide group (p = 0,046).

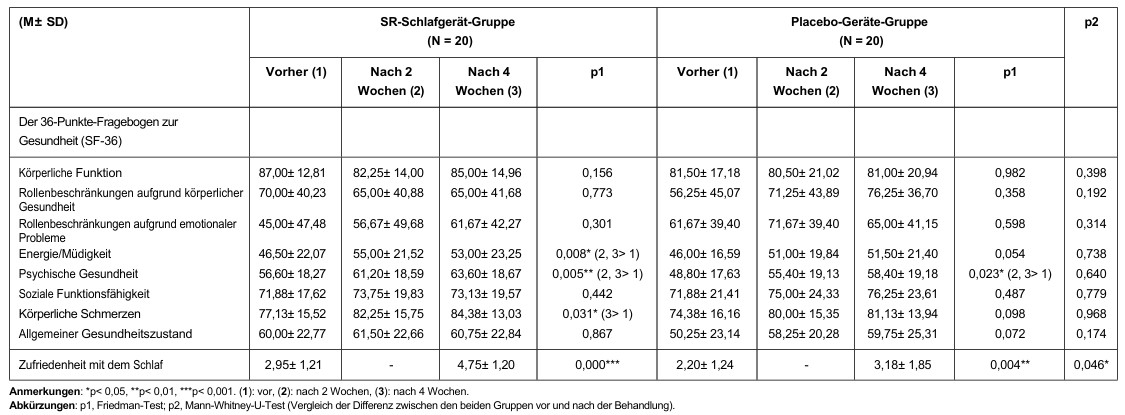

Comparisons of subjective quality of life (SF-36) before, 2 weeks after, and 4 weeks after using the SR sleep device/placebo device are shown in Table 4. Significant improvements in energy/fatigue (p = 0.008) and physical pain (p = 0.031) were observed in the SR sleep device group, but not in the placebo device group. We observed significant improvements in mental health (pSR = 0.005; pPlacebo = 0.023) in both groups. Sleep satisfaction improved significantly in both groups (pSR <0.001; pPlacebo = 0.004). Furthermore, the change in sleep satisfaction score from baseline (p = 0.046) was greater in the SR sleep device group than in the placebo device group.

Table 3: Differences in subjective sleep measurements in the SR Sleep device/placebo device group

Table 4: Differences between the health survey (SF-36) and sleep satisfaction in the SR-Sleep device/placebo device group

Of the 46 participants, two experienced headaches and dizziness when using the device (1 belonged to the SR sleep device group and 1 to the placebo device group) and discontinued participation. There were no other adverse events.

This study investigates whether 40 participants with sleep disorders can achieve improvements in subjective and objective sleep measurements after four weeks of using an SR sleep device/placebo device. Only two participants suffered from side effects such as headaches and dizziness (study group n = 1; placebo group n = 1) and discontinued the study. This study is the first to investigate whether SR affects sleep and sleep disorders.

In the SR sleep device group, both objective PSG measurements (SOL and TST, but not SWS) and subjective sleep measurements (SOL, TST, SE, sleep quality, daytime sleepiness, sleep satisfaction) improved significantly after using the SR sleep device. In the placebo device group, however, objective sleep measurements showed no differences after using the device, and there was only a subjective improvement in sleep in terms of sleep satisfaction and some components of the PSQI.

This result suggests that SR can reduce the symptoms of insomnia, particularly in terms of ‘falling asleep’ and ‘total sleep time’. Another important finding is that 55% of the placebo group showed improvement according to the PSQI and sleep satisfaction scale, which can be explained by the usual placebo effect in the treatment of insomnia.

At present, we do not yet fully understand the mechanism of SR in improving insomnia and sleep. Previous studies have shown that changes in geomagnetic activity are associated with epileptic seizures, myocardial infarction, stroke, and depression. Biogenic magnetite provides a molecular mechanism for geomagnetic perception that has been found in the human brain.

Cherry (2002) suggested that SR, which propagates extremely low frequency (ELF) waves globally, is ‘the possible biological mechanism’ that explains the biological and health effects of geomagnetic activity on humans. The peak frequencies of SR are subject to moderate daily variation of approximately ± 0.5 Hz. Interestingly, the first four SR modes happen to lie within the frequency range of the first four EEG bands (i.e., delta 0.5–3.5 Hz, theta 4–7 Hz, alpha 8–13 Hz, and beta 14 to 30 Hz).

Some studies have also found that human brain waves and SR have the same frequency range. The human body recognises, absorbs and responds to natural EMF through the process of frequency resonance matching. Through this matching, natural EMF can influence biological communication phenomena in cell-to-cell communication in the human body. 44 Pall (2013) also reported that exposure to EMF would promote Ca2+ influx via the voltage-gated Ca2+ channel, which can increase Ca2+ concentration in the cytosol and then cause biological effects.45 Wang (2019) also pointed out that extremely low-frequency magnetic stimulation can induce low-frequency activities and lead to resonance effects in the human brain.

The ‘biophysical mechanism’ for the mechanism of action on human health could explain the biological and health effects of geomagnetic activity. More and more psychiatrists are integrating electrophysiotherapy treatments into their clinical practice because they are non-invasive, have few side effects and can treat anxiety, depression and insomnia at the same time. Our findings on SOL improvement suggest that SR can resonate participants’ brain waves with 7.83 Hz waves and relax their bodies, making it easier for them to fall asleep and increasing their total sleep time. Another hypothesis is that EMFs are related to human melatonin metabolites, which could also explain the improvement in participants’ total sleep time and sleep quality after four weeks of treatment. However, this study did not show a significant increase in deep sleep percentage (SWS %). This could be related to the small sample size or the first-night effect of PSG. The four-week treatment period may be too short or may not yet have an effect on melatonin. Therefore, these results and hypotheses require more rigorous and long-term investigation. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of CBTi showed significant effects on daytime symptoms, including daytime sleepiness, although the effect size is only small to moderate. By improving night-time symptoms, CBTi may have a positive indirect effect on daytime symptoms. Similarly, the SR sleep device group in this study had a significant effect on the severity of daytime sleepiness, meaning that SR can improve the quality of life of insomnia patients during the day (e.g., energy/fatigue, physical pain, and mental health). In addition, Kay reported that SR improves depression.

In addition to the potential benefits for sleep demonstrated by this study, further therapeutic effects of SR, such as improved daytime sleepiness and depression, as well as the role of SR in these correlated conditions, need to be further investigated. Although this is a randomised, double-blind design, there are still limitations. First, the sample size was very small (N = 40), although we did reach the estimated sample size (N = 38). Second, several patients had received hypnotics and were unable to discontinue them, but they maintained the same medications and doses throughout the study. Sampling errors may occur if we only include participants who are not taking medication. Thirdly, the ‘first-night effect’ should be taken into account when performing PSG, as it may explain the improvement in PSG. However, only the SR sleep device group showed a significant improvement in PSG, and this finding supported the effect of SR on sleep. Furthermore, we cannot truly verify compliance, but we did instruct our participants to turn on the device every night during the study period.

This study shows that SR can reduce the symptoms of insomnia, which is confirmed by both objective and subjective measurements, although the sample size is small. Future studies should investigate the potential psychological and physical effects of Schumann resonance with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods to verify its effectiveness and side effects and to explore possible mechanisms.

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the first author or corresponding author after obtaining approval from the Chang Gung Hospital Ethics Committee. In addition, anonymised data from individual participants are available upon contacting the first author or corresponding author by email. The data are available immediately after publication with no end date.

This study was conceived by Professor Guilleminault prior to his passing on 9 July 2019. Although he was unable to serve as the corresponding author of this study, we would like to express our gratitude and appreciation to him. He was one of the most important and fundamental figures in the field of sleep medicine. Without his inspiration and vision, we would not have been able to complete this study. This study was supported by grants No. CMRPG 3J 0131 and 3J 0133 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital to Dr Yu-Shu Huang and grant No. CMRPG 3L0291 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital to Dr Wei-Chih Chin.

The authors declare that they have no financial arrangements or connections related to this study. This research did not receive any specific grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding institutions. Patent TW M530656 U (SR device) belongs to Professor Ling-Sheng Jang. The authors declare no further conflicts of interest in this paper.

1. Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia. Lancet. 2012;379:1129–1141. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60750-2

2. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders.

3rd edition. Darien (IL): American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. 3. Bertisch SM, Pollock BD, Mittleman MA et al. Insomnia with objectively short sleep duration and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality: Sleep Heart Health Study. Sleep. 2018;41:zsy047. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsy047

4. Generaal E, Vogelzangs N, Penninx BW, et al. Insomnia, sleep duration, depressive symptoms, and the occurrence of chronic musculoskeletal pain in multiple locations. Sleep. 2017;40:zsw030.

5. Hein M, Lanquart JP, Loas G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of type 2 diabetes in people with insomnia: a study of 1311 individuals referred for sleep investigations. Sleep. 2018;46:37–45. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2018.02.006

6. Harvey AG. Insomnia: symptom or diagnosis? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:1037–1059. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00083-0 1122 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S346941 Nature and Science of Sleep 2022:14 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) DovePress Dovepress Huang et al

7. Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–19. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

8. Dolsen MR, Asarnow LD, Harvey AG. Insomnia as a transdiagnostic process in psychiatric disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;16:471. doi:10.1007/s11920-014-0471-y

9. Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD et al. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: a clinical practice guideline of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:307–349. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6470

10. Morin CM, Jarrin DC, Ivers H et al. Incidence, persistence, and remission rates of insomnia over a 5-year period. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2018782. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18782

11. Maust DT, Lin LA, Blow FC. Benzodiazepine use and misuse among adults in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70:97–106. doi:10.1176/ appi.ps.201800321

12. Agarwal SD, Landon BE. Patterns of benzodiazepine prescribing in outpatient care in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e187399. doi:10.1001/ jamanetworkopen.2018.7399

13. Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, et al. The efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1335–1350. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0251-z

14. Glass J, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, et al. Sedatives and hypnotics in elderly people with insomnia: meta-analysis of the risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331:1169. doi:10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47

15. Edinger JD, Arnedt JT, Bertisch SM, et al. Behavioural and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17:255–262. doi:10.5664/jcsm.8986

16. Ong J, Sholtes D. A mindfulness-based approach to treating insomnia. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66:1175–1184. doi:10.1002/jclp.20736

17. Gong H, Ni CX, Liu YZ, et al. Mindfulness meditation for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Psychosom Res. 2016;89:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.07.016

18. Carotenuto M, Gallai B, Parisi L, et al. Akupressurtherapie bei Schlaflosigkeit bei Jugendlichen: eine polysomnographische Studie. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:157. doi:10.2147/NDT.S41892

19. Yeung WF, Chung KF, Poon MMK, et al. Akupressur, Reflexzonenmassage und Ohrakupunktur bei Schlaflosigkeit: eine systematische Übersicht randomisierter kontrollierter Studien. Sleep Med. 2012;13:971–984. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2012.06.003

20. Sok SR, Erlen JA, Kim KB. Effects of acupuncture therapy on insomnia. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:375–384. doi:10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02816.x

21. Yin X, Gou M, Xu J, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture treatment for primary insomnia: a randomised controlled trial. Sleep Med. 2017;37:193–200. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.02.012

22. Kirsch DL, Nichols F. Electrotherapy stimulation of the skull for the treatment of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. Psychiatric Clin North Am. 2013;36:169–176. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2013.01.006

23. He Y, Sun N, Wang Z, Zou W. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on insomnia: a protocol for a systematic review. BMJ open. 2019;9:e029206. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029206

24. Belisheva NK, Popov AN, Petukhova NV, et al. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of the effects of variations in the Earth’s magnetic field on the functioning of the human brain. Biofizika. 1995;40:1005–1012.

25. Mulligan BP, Suess-Cloes L, Mach QH, et al. Geopsychology: Geophysical Matrix and Human Behaviour. Man and the Geosphere, Nova Science Publishers; 2010:115–141.

26. Wang CX, Hilburn IA, Wu DA, et al. Transduction of the Earth’s magnetic field, detected by alpha band activity in the human brain. eneuro. 2019;6(2):ENEURO.0483–18.2019. doi:10.1523/ENEURO.0483-18.2019

27. Sentman DD. Schumann resonances. In: Volland H, editor. Handbook of Atmospheric Electrodynamics. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1995:267–298.

28. Cherry N. Schumann resonances, a plausible biophysical mechanism for the effects of the sun on human health. Nature Hazards. 2002;26:279–331. doi:10.1023/A:1015637127504

29. Persinger MA. Schumann resonance frequencies in quantitative electroencephalographic activity: implications for Earth-brain interactions. Int Lett Chem Phys Astron. 2014;11:24–32. doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/ILCPA.30.24

30. Ghione S, Mezzasalma L, Del Seppia C, et al. Do geomagnetic disturbances of solar origin influence arterial blood pressure? J Hum Hypertens. 1998;12:749–754. doi:10.1038/sj.jhh.1000708

31. Burch JB, Reif JS, Yost MG. Geomagnetic disturbances are associated with reduced nocturnal excretion of a melatonin metabolite in humans. Neurosci Lett. 1999;266:209–212. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(99)00308-0

32. Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual with standardised terms, techniques, and scoring systems for the sleep stages of humans. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1968;55:305–310.

33. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:193–213. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

34. Tsai PS, Wang SY, Wang MY, et al. Psychometrische Bewertung der chinesischen Version des Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) bei primärer Insomnie und Kontrollpersonen. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(8):1943–1952.

35. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi:10.1093/sleep/14.6.540

36. Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validation of the SF-36 health questionnaire: a new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305:160–164. doi:10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160

37. Koffel EA, Koffel JB, Gehrman PR. A meta-analysis of cognitive behavioural therapy in groups for insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:6–16. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2014.05.001

38. Persinger MA, Psych C. Sudden unexpected death in epileptics following sudden, intense increases in geomagnetic activity: prevalence of the effect and possible mechanisms. Int J Biometeorol. 1995;38:180–187. doi:10.1007/BF01245386

39. Stoupel E, Abramson E, Sulkes J, et al. Relationship between suicide and myocardial infarction in relation to changing physical environmental conditions. Int J Biometeorol. 1995;38:199–203. doi:10.1007/BF01245389

40. Feigin VL, Nikitin YP, Vinogradova TE. Solar and geomagnetic activities: Is there a connection with the occurrence of strokes? Cerebrovasc Dis. 1997;7:345–348. doi:10.1159/000108220

Um Ihnen ein optimales Erlebnis zu bieten, verwenden wir Technologien wie Cookies, um Geräteinformationen zu speichern und/oder darauf zuzugreifen. Wenn Sie diesen Technologien zustimmen, können wir Daten wie das Surfverhalten oder eindeutige IDs auf dieser Website verarbeiten. Wenn Sie Ihre Einwilligung nicht erteilen oder zurückziehen, können bestimmte Merkmale und Funktionen beeinträchtigt werden.